Reveron

In November 1951, Venezuelan Margot Benacerraf interrupted her film studies in Paris to create her first work, Reverón, a poetic study of the legendary and eccentric Venezuelan artist. The 30-minute short gained international acclaim when it premiered at the 1953 Berlin Film Festival.

In the summer of 1951, after completing my first year at the IDHEC, I was called back to Caracas because my father was gravely ill. Fortunately, he recovered, but while I was there I happened to meet the cultural attaché from the French Embassy, and it was through this connection that I came to make my first film, Reverón — a film made without benefit of technical preparation, without having even touched a camera, without having so much as made a two-minute student film, though of course by that time I had seen many films and had a feeling for what I wanted to say and do with my own.

Gaston Diehl, the attaché, told me that he was a great friend of Alain Resnais, whom he was trying to convince to come to Venezuela to do a film about a local painter, Armando Reverón, in whom I was also very interested. Resnais, who had just made Van Gogh, his first film about painting, was then starting Guernica, as it turned out, so he had to decline. Diehl asked me about Reverón, and I told him that, like everyone else with my interest in art, I had once visited him at his house.

In those days, Reverón did not enjoy the stature he does today, when several rooms in the national art museum are dedicated to his work, when his paintings travel abroad as part of international exhibitions. Though he has always been a great painter, at that time his greatness was recognized in a much more informal way. People would trek out to Macuto to visit him on Sunday afternoons as a kind of diversion. They would buy one of his paintings for a song and laugh at his eccentricities. They called him El Loco de Macuto. This was in 1951! No one imagined the trajectory that lay behind his art.

So Diehl proposed that I take on the project, since I was interested in film. I said I would be honored, but I made it clear that only in November, when I would be returning to the IDHEC, would I begin my technical studies. He still wanted to entrust the project to me. I proposed to make a preliminary trip to see Reverón, after which we would collaborate on the screenplay. That’s why Diehl’s name appears in the credits, as an acknowledgement that he inspired the project, though as it turned out he did not have a hand in writing the screenplay.

Macuto, a seaside resort which today is easily accessible by freeway from Caracas, back then was at least three hours by car on terrible roads. But this project implied another kind of distance as well — a distance from social propriety and compliance with parental expectations. Society in those days was much more conservative, of course. My parents were already upset with me because sending a girl to study outside the country simply wasn’t done — and studying film was beyond human comprehension! So nothing was easy for me, not even writing, because I was always regarded as transgressing “normal” limits. Women of my generation finished sixth grade and got married. To get a high school degree was not normal, and to seek a university diploma even worse. So, when I told them I was traveling to Macuto by myself to see a crazy painter and write something about him … well, I think I caused my parents a lot of anguish. As Spaniards transplanted to a very provincial society, my parents were doubly closed-minded.

It was very difficult to prepare the script because none of Reverón’s works had been catalogued. To compile a list of them, I literally had to go door to door asking people what they had and requested permission to photograph the paintings with my little still camera. How often I found what are now regarded as great masterworks stashed out in someone’s garage, being gnawed by rats…

To this day, my film stands as the only serious study of this artist’s work filmed during his lifetime. I shot my film in late 1951. In 1952, Reverón was committed to a psychiatric hospital where he was subjected to electroshock therapy. He died in 1954.

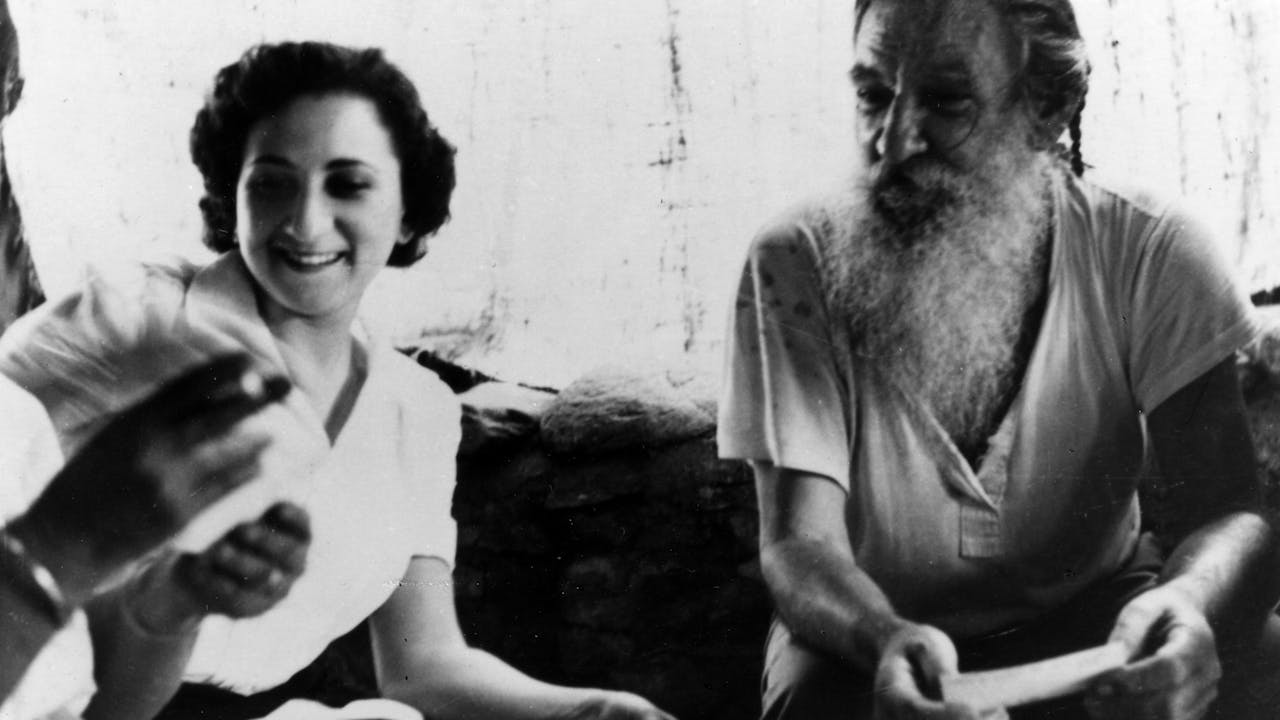

At the inception of the project, I spent a lot of time talking with Reverón, not just so he would trust me, but also because he had no idea what cinema was. He thought I was just going to take some photographs of him and then go home, like the others, because already foreigners had begun to arrive and take pictures. To my great horror and consternation, on my first visit his long-time model and companion, Juanita, appeared in a bikini with a feather in her hair. When I asked her about her costume, she said that a foreign journalist had visited recently and asked her to dress like an Indian for his photographs! Out of long, rambling conversations with Reverón, I attempted to assemble as much history and documentation on each of the paintings as possible. I remember this phase as very intense, very beautiful.

I wanted to establish such an intimacy with him, and to make my presence seem so natural, that when we started to shoot he would neither be conscious of the camera nor aware when I was directing — because, make no mistake about it, every take is directed in Reverón. It is very important to emphasize that neither of my films are documentaries in the classical sense. I don’t simply film what transpires in a certain environment and then assemble the material; I script everything on paper beforehand and direct as if I were filming a fiction film. I still leave myself room to maneuver, so that if something spontaneously comes along that fits within my narrative line, I’m able to incorporate it, but from the beginning of the shooting I am very clear what I want to film.

In Reverón, everything is orchestrated to fit into a 24-hour time span. In the editing room, I gave every hour a different color so as not to collapse my predetermined time scheme. For me, the optical track has always been a crucial element. In this instance I recorded the sounds in Venezuela and mixed the soundtrack in Paris for technical reasons. The man who composed the music, coincidentally, had also done the score for Alain Resnais’s Van Gogh. Guy Bernard had to work with all these sound effects which I brought from Venezuela, and some were pretty exotic, like the sounds I had recorded of the ceremonies of witches and healers, which we inserted during the late-night studio sequence to add to the general hallucinatory mood. Bernard was able to combine both his own musical compositions and elaborate sound effects to create the richly textured score that I was seeking.

My idea from the start was not to make a documentary about Reverón but to develop an essay on film as I would on paper, that is, specifically, to investigate through the filmmaking process the moment of creation and the relationship between creativity and madness… Given his precarious mental state and recurrent crises, he hadn’t painted for three years. It was both difficult and delicate to try to convince him to paint again. He would tell me, “You see, this hand says to the other hand that it can’t paint right now,” and there was no counterargument I could make that he couldn’t nullify by telling me, “I have here some horrible animals that don’t want me to paint yet.” His experience of that prohibition was so physical, so visceral. I had to have a lot of patience.

The script develops three parallel themes: tropical light, Reverón’s life, and his paintings. The 24-hour cycle is very calculated. The dawn is simultaneously the beginning of Reverón’s life, the beginning of the day, and the beginning of his oeuvre. Midday coincides with his most important period: the middle of his life, the glaring tropical light, and the white period, which represents a midpoint in his artistic evolution. I developed a natural curve in which the three parallel lines coincided.

The self-portrait that he eventually painted for me, which we filmed in process, turned out to be his last.… The actual filming lasted only about two weeks. The preliminary research phase, of course, took much longer, as with Araya. I had to move to Macuto, where I took a pension with my cinematographer, Boris Doroslovacki, a Yugoslavian who had worked at the UFA Studios in Germany and then filmed for one of the big Venezuelan oil companies before going on to found Caribe Laboratories. We were a two-person crew.

… I realized that I had to go live in Reverón’s house. So I brought my hammock and set myself up in the studio that is shown in the film. Reverón’s private quarters were located in a series of huts behind the main house, so this was not a great inconvenience to him. Even spending all of my time on site, the filming was still very difficult. Between all the waiting during Reverón’s frequent fits of madness, and running out of film stock when he felt well enough to paint (because the producers could only see their way clear to send me small amounts of film each time), I got pretty desperate. The shortage of film taught me to be very economical.

I shared the studio with a group of life-size dolls that he had made, rather phantasmagorical company in the late-night hours. He called each of them by name, and hade made them elaborate individual wardrobes. I knew that I didn’t want to film his attacks of madness directly; it seemed too invasive. So I decided to channel the madness through the hallucinatory power of the dolls. A psychiatrist recently commented on my strategy of filming in circles and spirals. I enter, circle around the house, then around the studio, around the painter himself, and finally into the mirror. According to the psychiatrist, this circular movement is a sign of madness. For me, it was an instinctive strategy for getting close to Reverón.

Eventually the two of us established a deeper understanding. He began to see that cinema was like painting when he observed how the lighting we created would fall on particular objects, and when he got a feel for the frame of the camera. Once he made these connections, a real complicity developed between us. He became quite fond of me. I realized this when he made the most loving, trusting gesture possible by offering me the keys to the trunks containing the dolls’ trousseaus. I felt I was violating his trust by deciding to film the circle dance [la ronde] with the dolls, so Boris and I made collapsible stands of wood, which allowed the dolls, when suspended, to rotate, and I kept my strategy hidden. We shot those sequences late at night, after Reverón had gone to bed.

On the last day of filming, in December 1951, it was 2:00 A.M. before Reverón finally finished his self-portrait. During the day he had locked himself in his hut and we didn’t know what he was up to, but when we thought we were finally through with the shooting, he said to me, “Margocita, now we are going to finish the film together. Before the words ‘The End’ you are going to put in what I have made. First you are going to appear as a priest and pardon all the dolls for their sins, and then the curtain may fall.” (He had never been to the movies, so this is how he thought they concluded, just like a play.) He assembled all the dolls as if they were in a cathedral, and decked out in my robes, I had to pass down the aisle between them, blessing and pardoning them all. Reverón watched me intently, and every once in a while he would interrupt, saying, “This one, Menequir, the oriental princess with the bracelets, she is the biggest sinner of all, and you have not pardoned her enough,” and I would have to go back and repeat the ritual. I had signaled Boris not to film because we were so low on stock and needed to save some to shoot the last exteriors the next morning. Reverón said suspiciously at one point, “Margocita, you are fooling me, because I don’t hear the little noise you make when you are filming me.” What could I say to that? I mumbled that something strange must be going on because I didn’t hear it either.

As we prepared to leave, he told me to take the painting he had done at my request. The car was filled to overflowing with cameras and equipment, so I told him that I would come back for the painting the following Sunday. When I returned, I found that the director of the Fine Arts Museum had taken it, which made me quite sad since I felt a great deal of connection with that particular work.

Once the shot was completed, the same producers who had made our lives difficult by parceling out film stock in such miserly fashion continued with more of the same. Henry Nadler, of Aguila Films, one of the producers, decided not to pay us our salaries. Boris was furious and refused to hand over the exposed film which he kept in a box at his house for almost a year, a very risky move in the tropics…

Meanwhile, I wrote to the IDHEC asking to be reinstated. In my enthusiasm for the Reverón project, I had postponed by return. Class had resumed in November 1951, and it was now February 1952. It was imperative for me to return, because I had seen there was no infrastructure to support filmmaking in Venezuela, and if I was to work in France I would need my diploma from the film school… So I returned to Paris, worked like mad, passed the exam, and graduated — all this without ever having viewed a frame of the Reverón footage…

I felt desperate to see the developed film, for I knew I had captured something very important. So I worked out an arrangement by which Nadler would pay Boris and send the negative to me. Nadler was all too happy to sell me his interest in the endeavor and get rid of this “problem.” When the laboratory called to tell me that the images were indeed intact, the sense of relief was overwhelming.

On November 15, 1952, the film was screened a the First International Festival of Documentary Films on Art… Reverón won first prize, but I could not be there to receive it because I spent that day alone in Tangiers with my father, who died the following day…

In February 1953 I was invited to the first Berlin Film Festival. Though the political situation was still acute, with the city still in ruins and the “air corridor” separating East and West Germany, they still managed to mount this inaugural festival. I arrived in Berlin very late because of flight delays. I was alone and felt just as terrified as I had on my first forays into the Bowery. I rushed to the hotel, dropped off my suitcases, and hurried to the screening, arriving after Reverón had already started. When the lights came up, there was an enormous ovation, the biggest I had ever heard, and I began to cry. Bauer, the festival director, went up to the podium and called for “Herr” Benacerraf to join him. I couldn’t get up because of the trembling in my legs, and of course, I was still crying, but even had I been able to compose myself, I was still draped in black, in mourning for my father, as was the Spanish and Latin American custom at the time. So I stayed in my seat.

As I was leaving the theater, I was intercepted by the French critic André Bazin, who introduced me to Bauer, an enormous, overweight man who looked at me (I am only five feet tall) as if I were an insect. “Where is your father?” he demanded. It was too macabre a story, so I simply said that my father was dead. “Why wasn’t I told?” he replied, “We would have organized a tribute!” It was then that I added, “My father died, but I was the one who made the film.” Bazin intervened to back me up, but despite his best efforts, this gender confusion persisted all the time I was in Berlin… Nevertheless, that festival changed my life because Lotte Eisner, the great specialist in German expressionism and the work of Fritz Lang, was in attendance. She was very enthusiastic about Reverón and wrote a glowing article in Cahiers du Cinéma.

One day, back in Paris, I received a phone call from someone who identified himself as “Langlois.” In my student days, I had stood in line to get into the old Cinématheque Français on the Avenue de Messine. Henri Langlois was a legend. “Which Langlois?” I replied into the receiver. I thought it was some kind of joke. He explained that Lotte Eisner had told him about my film, and he asked to see it. He later arranged to screen Reverón at the Cinématheque and gave a reception in my honor, which was where we finally met face to face. It was the beginning of an unforgettable friendship. He would later be very generous with his assistance when I founded the Cinemateca Nacional de Venezuela in 1966.

From that moment on, the film took off… At the end of the year, I returned to Caracas. I was just leaving the Museum of Fine Arts one day when I heard a voice calling “Margocita! Margocita!” Only one person called me that name. There stood Reverón, accompanied by his psychiatrist. He was dressed in an odd kind of jacket and pants, he had shaved his beard, his face looked completely different, and his ears seemed enormous. (I found out later that his illness made them grow.) He seemed altogether a different person, but he had recognized me instantly.

He began to call me every day, asking to see the film. I felt very ambivalent about showing it to him in his state, but I could not refuse. The screening was arranged for a Saturday morning at the biggest theater in Caracas at that time, the Cine Junín. So there we were, just the two of us in this enormous theater, plus his doctor and two males nurses.

At the beginning of the film, he laughed a lot, but later he became very quiet. I feared for how he would react when he saw what I had done with his dolls at night while he slept. After the film his doctor inquired brightly, “Well Reverón, it’s over. What do you think?” Reverón insisted that the film was not over, even though we had all seen “The End” appear on the screen. It had been almost two years, and who knows what he had been through, but he still remembered how he thought the film should and would end. “No, no, Margocita knows that it isn’t over,” he insisted, “because the dolls are still sinners; they were never pardoned.” I had to explain to his psychiatrist that Reverón was more lucid than either of us. And to Reverón I tried to explain that I hadn’t wanted to show myself in the film. But for him, it simply wasn’t finished. Within a few months of that encounter, he was dead.

-

REVERON

In November 1951, Venezuelan Margot Benacerraf interrupted her film studies in Paris to create her first work, Reverón, a poetic study of the legendary and eccentric Venezuelan artist. The 30-minute short gained international acclaim when it premiered at the 1953 Berlin Film Festival.

In the su...